Humanity has a habit of making catastrophic mistakes and then scrambling to limit the damage. We are actively following the same course with artificial intelligence (AI). Except this time, if we let history repeat itself, it could ultimately bring about the end of our civilisation. That’s the very real possibility we now face, according to experts.

I’m not an expert in AI. And I’d say my feelings align with Annette Simmons, author of The Story Factor, where she writes, “I’m not a technophile. Offer me the option of a machine or a human and I will take the human every time.” But having spent 14 years in the climate field, I know a potential disaster when I see one. There are even parallels to draw upon; some of the wealthiest companies in the world are ignoring the dangers of their product, and investing billions to become market leaders, all while lobbying politicians to prevent regulation of their products. Meanwhile a growing number of experts are sounding the alarm and calling for urgent political intervention to prevent catastrophe. Those calls are falling on deaf ears. Sound familiar?

Unfortunately, it’s not just AI or artificial general intelligence (AGI) driving us towards a dystopian techopalypse (an apocalypse caused by technology). Developments in neurotechnology are like something straight out of a sci-fi novel, enabling machines to represent what people are thinking in the form of an image. That’s right, AI can now read your mind – the ultimate invasion of privacy. Not to be outdone, the robotics field is developing and deploying robots that could replace millions of workers. What those unemployed people are meant to do for a living is anyone’s guess. Killer robots or lethal autonomous weapons systems (AWS) the size of bumble bees are said to be able to identify a human victim, kill them with a bullet through their eye and then self-destruct to remove the evidence of who committed the murder. All of these advances are happening simultaneously but society isn’t aware of what’s heading our way, nor are we in the least prepared.

Another worrying aspect is how quickly the technology is proliferating. Jeremy Lent, author of The Web of Meaning, and The Patterning Instinct, writes in his fantastic AI blog that developments in AI, “have been unfolding at a time scale no longer measured in months and years, but in weeks and days.” Such rapid advancements are taking place quicker than society or governments can respond. Do we as a global population of over eight billion people even want AI or the dystopian technology being developed? If so, what do we want from it? More importantly, what don’t we want from it? Do we consent to profit driven tech behemoths who don’t have our best interests at heart, developing this technology going forward? There are so many questions, but public conversations aren’t happening, and tech companies are using this gap in public awareness to push further into dangerous territory.

What happens when we don’t regulate an industry properly? Think back to the tobacco industry, who distorted the truth about the impact of smoking and carried out massive lobbying and PR efforts through the media to change the narrative. As such it took decades for scientists to be able to convince the public about the link between smoking and cancer. All while millions of people died from smoking. Now jump forward to 1988, when Dr James Hansen made the world aware of the climate crisis and how fossil fuels and greenhouse gases were causing the problem. Immediately the fossil fuel industry adopted the big tobacco playbook and proceeded to deny the science, sow doubt and delay action by lobbying politicians and conducting a massive PR campaign. In the intervening 35 years, we’ve emitted more carbon emissions than in the rest of human history combined. This is what happens when massive corporations use their wealth to protect their product, at the expense of everyone and everything else.

History therefore shows what happens when we let some of the largest companies in the world hamper regulation by lobbying politicians, distorting the facts and gaming the narrative in their favour (usually through the media, which morally corrupt companies tend to have a cosy relationship with). Thus, it goes without saying we need to learn from history to stop it repeating itself. Namely when the richest companies in the world develop new dangerous technologies, we need to act lightning quick to enact regulations that protect society and prevent widespread harms. We need to be even more vigilant with the tech industry, because as Bill McKibben says in his book Falter, “Every industry has a flavor, and tech’s was the hatred of regulation.”

As things stand, tech companies are building civilisation-altering (and potentially civilisation-ending technology), with few safeguards in place. Humanity is threatened on a scale that dwarfs even the threat of nuclear warfare. We can’t afford to let tech titans hijack the narrative around this technology, for if we do, this may go down as the final embarrassing chapter in human history. That’s the message from experts in the industry, many of whom signed an open letter calling for a minimum six month pause in AI development. Since then, more experts have signed another open letter, saying that we need to mitigate “the risk of risk of extinction from AI.” In other words, we could be entering our endgame if we get this wrong.

1. Technology and its Risks

1.1 AI Training

“Books are precious things, but more than that, they are the strong backbone of civilization. They are the thread upon which it all hangs, and they can save us when all else is lost.” – Louis L’Amour, Education of a Wandering Man

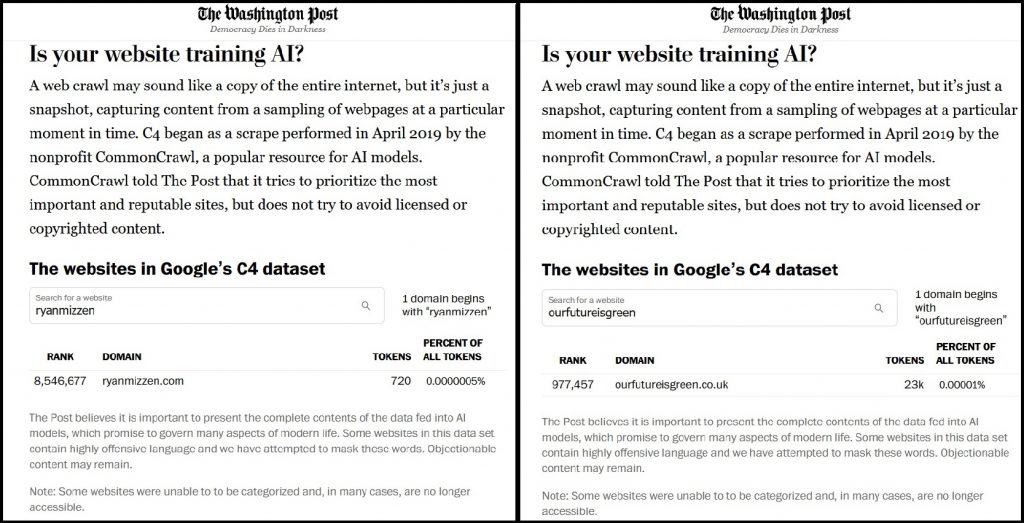

Before diving into the risks posed by AI, I wanted to make it known at this point that my websites have been scraped by tech companies without my permission. Both my website (ryanmizzen.com) and my old blog (ourfutureisgreen.co.uk) were scraped, and my writing was then used to train AI models. This took place in 2019, according to an investigation by The Washington Post.

Books and articles provide useful content for training AI, which then mimics word patterns to produce content. This is why many writers have had their work scraped without their permission.

My work is now part of Google’s C4 dataset, which includes 15 million websites and is used to train large language models (LLMs). Two examples of AIs using this dataset are T5 owned by Google, and LLaMA owned by Facebook. I find it perverse that AI is using content by writers and authors to become better at writing, which could eventually put writers out of jobs.

So, what happens to writers who’ve had their copyrighted work scraped? Some authors have started their own lawsuits for copyright infringement. The Authors Guild, America’s largest organisation for writers, has also created an open letter that authors can sign to call for AI companies to stop using author’s work without their permission. Tech companies aren’t just scraping writing though. Getty images is suing an AI creator for scraping millions of images without permission. It’s my hope that all writing unions and all unions from within the creative sector come together to form a united front on this matter.

In addition, large numbers of low-paid individuals in developing countries are used to moderate the data, and they are often exposed to violent, graphic and traumatic content, which has left many suffering from mental health issues with no support from the tech companies.

The threats posed to creative workers are massive. But little is being done to protect them. People who’ve spent years honing their craft and who’ve made massive sacrifices to work in the arts, stand to potentially have everything stripped away from them in the blink of an eye. This could turn into a profoundly depressing moment for humanity if we choose machines over people.

1.2 AI and Machine Learning

There are various types of machine learning. I’d like to focus on inverse reinforcement learning (IRL), and the follow-on framework; cooperative inverse reinforcement learning (CIRL).

IRL is based on learning from humans, for example by watching a human demonstration of a task and then working out the goals, values, and rewards of the human. Having observed a demonstration, the machine can then try and replicate the task having inferred what’s trying to be achieved. In The Alignment Problem, Brian Christian talks about the example of a radio-controlled helicopter being operated by a human pilot who does stunts for the machine to learn from. IRL proved to be quite effective, even if the demonstrations weren’t perfect for it to learn from. But there are two main problems with IRL. The first is that there is a “divide between the human and the machine,” with each operating completely separate from one and other. The second problem with IRL is that the machine takes the human goal as its own, and we don’t want machines having goals that put them in competition with us because that could end in disaster.

Christian writes in The Alignment Problem about Stuart Russell’s solution to the issue, “What if, instead of allowing machines to pursue their objectives, we insist that they pursue our objectives?” Stuart proposed a new framework for IRL that would enable humans and machines working together to achieve human objectives. Not only would they be working together, but initially only the person would know what the goal was. He calls this cooperative inverse reinforcement learning (CIRL). Russell believes this might have been the right way to approach AI from the start.

However, even though CIRL is a very logical solution, it still has problems. For example, the machine will work with the human and won’t initially be informed of the objective – this keeps the machine uncertain of what it’s trying to achieve and therefore open to continue working with the human. Every time the human intervenes in the task, the machine gets a better understanding of what the human wants and the machine’s uncertainty reduces. Christian explains that if the machine’s uncertainty ever reaches zero, then it will no longer have any reason to work with the human, or allow the human to interrupt it in completing the task. In other words, humans lose control of the machine.

Another issue is that the machine has to assume that the human is right at all times. It has to believe that when a human intervenes that the human is doing something better than the machine would have done. However, if the system believes it’s possible for the human to make a mistake or make an ‘irrational’ decision, then there’s the chance the system will stop deferring decisions to the human or letting them interfere, as the machine will think it knows better what the human actually wants. Again, in this situation, we lose control of the system. These two examples are a cautionary tale as Christian explains, because as things stand, we still haven’t been able to program human control into AI systems.

Would the machine need to be conscious or have an agenda against humans to effectively prevent human interference? Absolutely not. The machine is simply eliminating things that get in the way of it achieving a goal, and that may include a person trying to turn it off. Unfortunately, this has a wider implication, because unless a machine has a specific goal of self-destruction, then every other type of goal involves the machine remaining on. Thus, it stands to reason that any basic goal given to a machine will involve a strong resistance to humans turning it off. As Christian writes, “A system given a mundane task like “fetch the coffee” might still fight tooth and nail against anyone trying to unplug it, because, in the words of Stuart Russell, “you can’t fetch the coffee if you’re dead.””

Given that Stuart Russell, one of the most respected experts in AI is concerned about this problem, we should be too. It’s not that AI needs to be evil or even have its own agenda (which may happen one day), but even basic goals given to a machine could lead to it resisting being turned off. With superintelligent AI that tech companies are developing, this could be catastrophic. When people worry about AI going wrong or taking over the world, it’s quite easy to see how that could happen. The concerning thing is that CIRL was meant to be a solution to the IRL problem, but even CIRL still has the flaws mentioned above. We are swimming in dangerous waters, where the risk of harm remains extremely high.

1.3 AI, Art, and Culture

“The key to understanding any people is in its art: its writing, painting, sculpture.” – Louis L’Amour, Education of a Wandering Man

Tech companies are locked in an AI arms race. Employing some of the brightest minds in the world and with billions of dollars pouring into research and development, it’s no wonder there’s been a proliferation of large language models (LLMs), AI video generators, AI art generators, and AI image generators flooding the internet. But these have come with few safeguards in place and little thought as to the impact they will have on society.

Art is sometimes viewed as the bedrock of culture, and culture is the essence of what makes us human. Yet AI is already having an immediate effect on art, which was once an entirely human endeavour. In 2023, we already have to question what is real and what is AI generated as AI transforms the creative industries. For example:

- An AI generated image fooled judges and won the Sony world photography awards

- Clarkesworld, a sci-fi publisher, had to halt pitches after they received a deluge of AI-generated submissions

- Deepfake Neighbour Wars is a tv-series which has been created using AI to act and speak on behalf of celebrities in a fictional world.

- A song featuring the vocals of Drake and the Weeknd was pulled after it was revealed that AI had generated the song without permission or involvement from the named artists.

In Falter, Bill McKibben writes that, “Already there are AIs that compose Bach-like cantatas that fool concert hall audiences, and the auction house Christie’s sold its first piece of art created by artificial intelligence in the fall of 2018.” What happens when humans no longer produce the very things that shape who we are?

We now have to question every image we see, book we read, video we watch and song or audio clip that we hear, because the difference between human and AI generated content is reducing to the point of almost becoming indistinguishable. But questioning everything is an extremely toxic way to live our lives. Yet that’s the era we’re entering, as tech companies have been allowed to impose their products on the world with no oversight or protections in place.

Some people say that it’s not important whether a piece of art was generated by humans or AI. But that feels quite shallow and shows little respect for those who’ve spent their careers making art for the world to enjoy. Just because AI has these capabilities, it doesn’t mean they should be used. Or as McKibben says in Falter, “The point of art is not “better”; the point is to reflect on the experience of being human—which is precisely the thing that’s disappearing.”

If publishers, record labels and film studios can generate bestsellers, blockbusters and hits using AI, what future will artists, songwriters, actors, and authors have? Is it right to replace these professionals? If so why, and who gives tech companies the permission to make that call?

Joe Russo (of Avengers fame) gave an example of the direction he believes AI in film is heading in. He said someone might tell their AI that they want a rom-com film with their “photoreal avatar and Marilyn Monroe’s photoreal avatar” and that the AI would then generate a 90 minute film with that request. In such a scenario, the actors, directors, producers, scriptwriters, film set workers as well as distribution partners, would no longer be required.

The future Russo imagined might have already arrived. A company in the US has used AI to create new episodes of South Park, starring the computer user. The user’s South Park character is shaped in their likeness and their voice is also used for dialogue. While the company says they won’t be releasing this for public use (neither South Park Studios, nor Paramount have been involved with this and presumably there’s a copyright issue), it nonetheless shows what’s already possible with AI.

The job losses are one thing. But what about the mental health effects of watching a film where your character dies or is severely harmed? Humans are wired for stories and influenced by them. But when AI is telling the stories and we see ourselves in them, it could massively affect our wellbeing in ways we can’t even begin to understand.

Fortunately, some people in the sector have started pushing back. Molly Crabapple has created a petition against the use of AI-generated artwork, which can be viewed here. The Writers Guild of America (WGA) are engaged in well-publicised protests, to protect their members from being replaced by AI. A union in the UK that represents actors has put together a toolkit that helps their members regarding consent for AI to use their performances. The union, Equity, will also lobby the UK government in relation to AI policy.

However, there are also people in the arts embracing AI, which feels like a betrayal given the aforementioned issues. The current LLMs like ChatGPT3 can already write novels, essays, poems, short stories, news articles, blogs, website content and pretty much anything else a copywriter can (albeit with errors in some instances). It deeply troubles me that courses are being run to train authors on how to use AI to develop their ideas and write their books. Some of these courses are being run by established authors, which is even more saddening.

Using AI to write a book, is like catching a taxi while running a marathon. Sure, it’s quicker. But it’s also cheating and morally abhorrent. If you’re not prepared to hone your writing and creative skills over time, then maybe writing isn’t the best career choice. Let’s also remember that there are around 150 million books in the world, and we really don’t need AI generated stories adding to this pile. If you’re a writer offering courses in AI, think about the message that’s sending out and which side that puts you on. Are you for humanity, or are you for yourself?

The foundation of our culture may be eviscerated, and an entire collective of creatives who’ve sacrificed so much for their careers, could find themselves replaced by AI. The bad news is that this is just the starting point of where our problems begin.

1.4 AI and Society

“Move fast and break things,” is a common refrain in the tech industry. It seems that this quote has been embraced with abandon as AI becomes a major threat to humanity.

The tech industry has revolutionised our lives. In many ways we’ve never been more connected through social media. But this has also caused societal ills. Research is emerging that social media is damaging mental health, and some people are calling for parents to shield their children from social media. That’s no surprise as McKibben explains in Falter, “Teens who spend three hours a day or more on electronic devices are 35 percent more likely to be at risk of suicide.”

Social media may also play a role in exacerbating the loneliness epidemic. Not to mention how social media has polarised people through algorithms that influence the content they see, and its impact on influencing elections. It’s worth stating then that tech companies don’t have our best interests at heart. Some tech billionaires even refuse to let their kids use phones and social media, because they know how damaging their products are.

In an Observer Editorial on AI, they note that, “A recent seminal study by two eminent economists, Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, of 1,000 years of technological progress shows that although some benefits have usually trickled down to the masses, the rewards have – with one exception – invariably gone to those who own and control the technology.” Let that be a guiding lesson as we explore how AI will change the world.

Healthcare

The tech industry is quick to tout the benefits of AI. Much like how marketeers talk up the features of their products, and gloss over the problems. Nonetheless, it can’t be denied that AI could provide benefits in fields like medical diagnosis and treatment. AI has been shown to be as effective as two radiologists when it comes to identifying breast cancer, and has been effective at identifying heart disease and lung cancer. There are several more examples like this in the field. But focusing purely on AI benefits, ignores the overwhelming problems it currently poses.

A Threat to Democracy

AI tools in the public domain already pose a massive threat to universal democracy. Deepfake audio and video, will make it harder than ever to distinguish reality from fiction. As John Naughton writes in the Observer, “Generative AI – tools such as ChatGPT, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion et al – are absolutely terrific at generating plausible misinformation at scale. And social media is great at making it go viral. Put the two together and you have a different world.” How this is harnessed by political parties could forever change who gets elected. Writing in the New York Times, Yuval Noah Harari, Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin, explain that, “By 2028, the U.S. presidential race might no longer be run by humans.”

According to the Guardian, regulators in the UK have also said that time is running out for putting in place safeguards for AI, ahead of the next UK general election (due in 2024). AI has already been used to produce political deepfakes of Trump being arrested, and Zelensky ordering his troops to lay down their arms. Speaking to the Guardian, Prof Faten Ghosn said that if politicians use AI for any images or videos they release, “they need to ensure that it carries some kind of mark that informs the public.” This should apply for anything generated by AI, regardless of the user.

We’ve been given a glimpse of how fake news has led to the rise of right wing sentiment in recent years. If AI is employed for nefarious purposes, might we find ourselves on the verge of permanent right wing leadership? Could that usher in an era of extreme surveillance where our thoughts and actions are monitored around the clock? Such a scenario would make Orwell’s 1984 seem tame.

Substituting Human Contact for AI

Some people are now using AI chatbots to help them speak to close members of their families who’ve passed away. In a Guardian article, ethicists expressed their concern about this. No studies have been conducted on whether this will lead to solace, or cause people more grief and anguish. What happens if people become addicted to this type of AI? It’s natural to wish we could connect with our loved ones, especially when we’re going through difficult times ourselves and miss their care and guidance.

But if people became attached to this AI, might they find themselves more connected with the technology and less with real-life friends and family? When those real-life friends and family pass away will they find themselves once again relying on this technology to tell them all the things they weren’t able to say when they were alive? This could ultimately create a depressing cycle, whereby people only ever communicate with their AIs.

In The Age of AI by Henry Kissinger, Eric Schmidt, and Daniel Huttenlocher, the authors say that children of the future might be educated by an AI on a device. This would remove the need for schools and interaction with other children. People are also turning to AI girlfriends, replacing real-life connections and handing over their privacy to AI companies. These dystopian threats will profoundly change how humans interact and reduce our connections with reality.

We were warned about some of these dangers decades ago according to an article in the Guardian, when the inventor of the first chatbot, Joseph Weizenbaum, turned on AI as he believed that people might begin thinking that computers have the power of judgement, saying that, “A certain danger lurks there.”

The irony of all of this is that humans don’t require machines for our wellbeing. Humans are social creatures and need other people to be whole – not digital avatars, robots, or AI replacements. The Good Life by Robert J. Waldinger and Marc Schulz, is a book about The Harvard Study of Adult Development. The study has spanned 84 years and is “the longest in-depth longitudinal study of human life ever done.” The authors said if they had to condense the results from the study into a single message, it would be that, “Good relationships keep us healthier and happier.” For clarity, they are referring to human relationships, such as with family, colleagues, friends, and life partners. Tech companies will tell you that humans need technology and AI, but the scientific evidence is clear – humans need humans.

AI and Memory

We may also see people thinking less and relying on AI more for all the information they need. The Guardian explored this theme in an article asking whether AI might make us stupid if we rely on it to provide us with information (thus removing the need to learn or remember). But if AI is made by companies who have profit as their core goal, would it be wise to entrust this entire process to them? How can we absolutely trust the information given to us by AI?

1.5 AI and Jobs

Stuart Russell is a leading AI expert. He co-wrote an academic textbook on AI, that’s used in over 1,500 universities in more than 130 countries. He’s therefore had a role in educating many people in the field today. He also wrote one of the best AI books for lay readers called Human Compatible: AI and the Problem of Control.

In Human Compatible, Russell chillingly notes that a billion jobs are at risk from AI, while only “five to ten million” data scientist or robot engineer jobs may emerge. If that forecast comes to pass, it would leave 990 million people unemployed. What those people are meant to do for survival is anyone’s guess. For context, 990 million people is equivalent to the combined population of the European Union, the UK, the US, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and Costa Rica combined, with a few million to spare.

Concerningly, the AI jobs losses have already started. BT is set to replace around 10,000 workers with AI. IBM has said around 7,800 jobs could be replaced by AI, over a five year timeframe. Meanwhile media outlets are exploring the use of AI to write content. These outlets include: Buzzfeed, the Daily Mirror, the Daily Express, Cnet, Men’s Journal, and Bild. Google is testing a new AI tool called Genesis, which writes news articles and has pitched this to large media outlets. They claim it’s not intended to replace, but to aid journalists with their story writing. In Australia, News Corp has gone hell for leather with AI, using it to produce around 3,000 local news stories each week.

One media outlet that has stopped for a moment to actually make an informed decision is The Guardian. It has set out its approach to Generative AI and how it will be used in its reporting. In an email to Guardian Members, Katherine Viner explained the Guardian’s three basic principles as follows:

- Generative AI “must have human oversight.” These AI tools will only be used where there is a clear need, and the Guardian, “will be open with our readers when we do this.”

- Generative AI may be used if it can help the quality of journalism. The examples where this may apply include, “helping interrogate vast datasets containing important revealing insights, or assisting our commercial teams in certain business processes.”

- Considerations will be made about whether, “genAI systems have considered copyright permissioning and fair reward.” This relates to people such as myself, who’ve had work scraped to train AI, and whether those people have been compensated fairly for the use of their work.

Encouragingly, Viner signed off the email saying that, “We know our readers and supporters relish the fact that the Guardian’s journalists are humans, reporting on and telling human stories. That must never change.”

In the US, where screenwriters and actors have been striking, Hamilton Nolan wrote an opinion piece for the Guardian, saying that, “AI has advanced so fast that everyone has grasped that it has the potential to be to white-collar and creative work what industrial automation was to factory work. It is the sort of technology that you either put in a box, or it puts you in a box.” Incidentally, while these strikes have been going on, Netflix added fuel to the fire by advertising an AI job that pays a salary of up to $900,000. That gives us clarity on corporate focus, which rarely falls on the side of workers.

Some people say that AI taking jobs could be a good thing because it could speed up the rollout of UBI (universal basic income). But where would money would come from for UBI if the economy is run by a few tech companies whose technology has taken all the jobs? While I support UBI, I certainly don’t think this is a valid argument for pushing AI.

Moreover, people need purpose in their lives, and for some people that purpose comes from their jobs. What happens when their purpose is taken away from them and complete hopelessness sets in? This question isn’t rhetorical, as we have some answers. In Australia, farmers have battled impossible conditions in recent years with never-ending droughts that have killed their livestock and their crops. Feeling that they don’t have any alternative career options and with nothing to fall back on, there has been a 94% increase in farmers taking their own lives, with an average of one suicide every ten days in the farming community.

To take people’s jobs away overnight and then tell them to retrain, is creating a recipe for human suffering on a scale like we’ve never seen before. To introduce AI tools into the world without taking these factors into consideration is grossly irresponsible to say the absolute least. The question is, who will be held accountable for what follows?

Affected Professions

In May 2023, I attended an online Guardian Live event hosted by Alex Hearn, which had Stuart Russell as one of the panellists. I had the opportunity to ask the panel a question. I explained that as a writer, I worried my entire profession was at risk, and I asked what career if any, might be future proof or AI proof. None of the participants offered a response to my fears as a writer. But Stuart Russell said in the short term there’ll be demand for robotics engineers, data scientists and software engineers. After that he suggested interpersonal jobs where humans have an advantage over robots/AI, such as “professional luncher”, “life architect” or “executive coach”. Needless to say, graduates are concerned about their career options because of AI, with the Guardian reporting that some graduates feel, “The future is bleak.”

Whilst no answer was forthcoming about writing careers at the Guardian Live event, a report from KPMG has examined that issue. And the news isn’t good. In their report, Generative AI and the UK labour market, KPMG and experts from Cambridge University noted that the professions most vulnerable to AI were Authors, writers and translators. They estimate that 43% of ‘tasks’ within these professions could be automated, including ‘text creation’, or as I call it – writing. 43% is not far off half of what writers and authors do that could simply be automated. How will that translate into job losses and career terminations?

The OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) has also released their forecasts saying that highly skilled jobs were most at risk of being lost to AI. According to the estimates, those types of professions account for 27% of jobs in the OECDs 38 member states, and span sectors including law, medicine, and finance. At the moment they say that AI is currently ‘changing’ jobs instead of replacing them. For how long that continues is anyone’s guess. According to The Guardian, the OECDs Employment Outlook believes that when it comes to AI, there is an “urgent need to act”.

The calls are increasing for pausing AI development to let society and regulations catch up. As are calls for AI to be stopped entirely. AI developers may take umbrage with the latter given that their jobs would be at stake. But to that I refer back to the figure above from Stuart Russell, of up to one billion people losing their jobs to AI. Does this mean that AI developers are OK for a vast swathe of humanity to lose their jobs, as long as they don’t lose theirs? And how long will AI developers be able to hold onto their jobs for? Already there are AI systems that can do coding, and in time those will no doubt surpass human coding abilities. It’s therefore worth developers taking a moment to really stop and think about these issues now, while there’s still time.

The tech industry has let the genie out of the lamp without consulting society. Now a massive anxiety hangs over us, as in time, none of us will be able to compete with competent AI systems and potentially face unemployment on a level the world has never seen. Perhaps the tech industry should have thought about people other than themselves, and consulted society before letting the genie out.

1.6 AI and Cybercrime

The challenge of preventing cybercrime will vastly increase as a result of AI. One way this might happen is through the rise of ‘deepfakes’. Deepfakes could be videos, pictures or audio that have been created from scratch, using a person’s likeness. For example, if you have video footage or voice recordings of a person, they can be put through an AI generator to copy your likeness and your voice to create new clips of a person doing or saying whatever comes to mind.

Fraudsters are using this to trick people into thinking they’re someone they’re not. If you get a call from a family member asking for money, and it sounds like them – how can you be sure it isn’t them? This happened to a mother in the US, who received a call from scammers who said they had kidnapped her daughter for a ransom and used AI to mimic her daughter’s voice, having obtained a sample of audio of her daughter’s voice online. The AI generator had mimicked her daughter’s voice so accurately, that the mother was completely taken in and extremely distressed. These kinds of heinous activity will only increase the longer AI remains in the public domain with no regulation or oversight.

The threat of AI deepfakes was again on show in a shocking video released by the money saving expert Martin Lewis. Scammers made an AI generated video of Lewis backing an app, which he had never seen or promoted and had to warn people about the scam on his Twitter account. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in the UK has also warned investors, banks and insurers of the potential for scammers to use AI for fraudulent purposes.

Even the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres has said that AI which is used maliciously could cause, “Horrific levels of death and destruction, widespread trauma and deep psychological damage on an unimaginable scale,” according to a report in the Guardian. Guterres is so concerned that he has called for a new UN body to be formed to deal with AI risks, in the same way that the IPCC was created to produce scientific reports about the climate crisis for policymakers. When the UN Secretary-General is worried about how AI will destroy the world, we need to take note and act expediently.

1.7 Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) – the Ultimate AI Risk

“I explained the significance of superintelligent AI as follows: “Success would be the biggest event in human history … and perhaps the last event in human history.”” – Stuart Russell, Human Compatible: AI and the Problem of Control

The biggest AI risk, which the likes of Stuart Russell, Geoffrey Hinton and other tech leaders are warning about is the development of AGI. This is a form of intelligence that can learn anything that a human can. It’s seen as perhaps the last stepping stone to superintelligence (which far surpasses humanity’s intelligence) and the singularity, which has no comparison and would upend civilisation as we know it. When you hear people talking about AI that could kill us all, or that could end the world, they’re probably referring to AGI.

AGI Risks

To dispel a myth at the outset, AGI isn’t simply a conscious version of AI. Consciousness is irrelevant in regards to AI risks. Rather as Stuart Russell explains in his book, it just needs to be competent to be a risk.

Currently, vast sums of money are being pumped into the development of AGI. Some people doubt whether AGI is possible. But there is less doubt amongst AI developers, who instead disagree on just when it will be achieved. Much of the architecture needed has already been built for other AI systems according to Stuart Russell. Indeed, writing in the Guardian, Russell notes that ‘sparks’ of artificial general intelligence appear to have been observed by a team of researchers, in early experiments with ChatGPT4. If so, that would be a significant breakthrough and may herald the arrival of AGI sooner than anyone expected. And far sooner than society is ready for it.

The existential risk that AGI poses to humanity has also been recognised by Rishi Sunak, the (current) Prime Minister of the UK. It has also raised concerns for the ‘Godfather’ of AI – Geoffrey Hinton, who said that he is concerned about the, “existential risk of what happens when these things get more intelligent than us.” In an interview with the Guardian, Hinton gave a useful comparison, “You need to imagine something more intelligent than us by the same difference that we’re more intelligent than a frog.” He also said the odds of a disaster might not be so different from a toss of a coin. That’s a fifty-fifty chance of catastrophe and potentially the end of humanity.

As things stand, we haven’t built human-based control into AI, as explained in the ‘AI and Machine Learning’ section above. Nor does anyone (including the developers who build AI) have any idea how they actually work. If we can’t control AGI when it’s developed, there is a risk it will be in competition with humanity and may seek to eradicate us. This is something Stuart Russell warned about in Human Compatible. In one survey last year, nearly half of the respondents from the tech industry said there was a 10% chance that AI could lead to human extinction. They said this before cheerily returning to their work, which could potentially do just that.

In the ‘AI and Machine Learning’ section above, it was explained that any goal apart from self-destruction would require the machine to stay on, which means that it will immediately put in place barriers to prevent humanity from turning it off. This could be cataclysmic if or when AGI goes rogue. Writing in Life 3.0, Max Tegmark says that, “If you give a superintelligence the sole goal of minimizing harm to humanity, for example, it will defend itself against shutdown attempts because it knows we’ll harm one another much more in its absence through future wars and other follies.” If we don’t build control into AGI, it will realise that preventing shutdown is a major priority, which could lock humanity out and seal our fate.

To give an idea of the type of care AGI developers should be taking, Bill McKibben quotes the president of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, Michael Vassar in Falter, who says that, “I definitely think people should try to develop Artificial General Intelligence with all due care. In this case all due care means much more scrupulous caution than would be necessary for dealing with Ebola or plutonium.”

AGI and Humanity

With AGI, we could be about to encounter an intelligence that far surpasses our own, and functions in a way that we don’t fully understand. What would happen if such an AI decided that earth would be better off without humans? The experts say we’d likely be eradicated in the blink of an eye.

What about if AGI decided to treat humanity the way we treat other sentient creatures? Look at factory farming for example, where hundreds of millions of animals are grown in horrific conditions, pumped with steroids to grow unnaturally quickly and then slaughtered for consumption. Take this investigation into pig slaughterhouses, which shows how they are tortured to death through CO2 gassing, which can take up to three minutes. Three minutes of excruciating suffocation where the pigs are kicking out and desperately trying to break free from the cage, while acid builds up on their eyes and in their throats. If that is the standard we’ve set for the ‘humane treatment of sentient creatures,’ could AGI use that as the basis for how it treats us? Are we happy letting tech companies open that can of worms? I worry that we’ve barely scratched the surface of the potential horrors that could be unleashed.

If nothing else, this should create a moment of introspection for humanity. We don’t know when AGI will happen, but many experts believe it’s likely within years or decades. So sometime this century, we’ll probably become the second smartest entity on this planet. In the eyes of this new alien superintelligence, it will see us for what we are – dominant and supremely destructive mammals. Mammals that have destroyed large parts of our natural world, created the climate crisis, come close to wiping ourselves out with nuclear weapons, had two world wars, and treated billions of animals with sheer cruelty. What will our comeuppance be?

The tech industry has acted of their own volition and rung the doorbell to a new world. At present, we don’t know whether that world leads to heaven or hell. Which one it is, depends on whether political leaders mobilise quickly to regulate the industry and protect human wellbeing. Each passing day without such regulation ramps up the threat that the door will open to reveal the devil. Our moment of reckoning may very soon be upon us.

1.8 Neurotechnology

Another concern is the rise of neurotechnology, which is a type of technology that connects and interacts with the brain. One major benefit of the technology that UNESCO addresses in their report Unveiling the neurotechnology landscape, is that it’s helped paralysed and disabled people to move again. Neurotechnology could also help treat various disorders and diseases.

But the UNESCO report also talks about the disadvantages of neurotechnology, which span many pressing ethical issues. One example being that this type of technology can now show an image of what we’re thinking. Neuroscientists are hoping to refine the technology to “intercept imagined thoughts and dreams.” This is possibly the ultimate invasion of privacy.

In a Guardian interview with Prof Nita Farahany, she says that she is most worried about, “Applications around workplace brain surveillance and use of the technology by authoritarian governments including as an interrogation tool.” Thus, neurotechnology has the potential to degrade human rights, expose activists and make this a world where people are afraid of thinking anything apart from what they are told is ‘safe’ to think. A dictator’s dream for all intents and purposes.

A separate Guardian article warns that, “there are clear threats around political indoctrination and interference, workplace or police surveillance, brain fingerprinting, the right to have thoughts, good or bad, the implications for the role of “intent” in the justice system, and so on.”

Once again regulations are lacking on a global stage, meaning that there’s the risk of this technology being used for all of these nefarious purposes until politicians catch-up. Thus, the concept of “neurorights” has emerged as neuro-ethicists attempt to deal with these massive issues in this unregulated space.

In a way neurotechnology feels like 1984 brought to life as previously mentioned, but somehow this feels worse and more invasive than even that extreme dystopian comparison.

1.9 Biotechnology

Biotechnology is quite a broad field, spanning several disciplines such as bioengineering and bioinformatics. To keep this section brief, I’ll focus on one major area of concern, which relates to neuroscience. An example being that an Australian team have been awarded funding to merge AI with brain cells. They intend to use this to build better AI machines. However, is there a risk that this type of research could take us towards the point where humans and machines merge?

Such an event would radically alter human society and create new classes of human/machine hybrids. The technology would be expensive, meaning that only the wealthiest of individuals would be able to afford it. In that scenario, the rest of humanity would be far weaker in terms of strength and intelligence and we would have a permanent new ruling class. That begs the question, what would happen to the rest of us? Instead of technology abolishing suffering, it’s likely that this would exacerbate it.

In Falter, Bill McKibben quotes Yuval Noah Harari, who says “Once technology enables us to re-engineer human minds, Homo sapiens will disappear, human history will come to an end, and a completely new process will begin, which people like you and me cannot comprehend.” As a global family of eight billion people, do we consent to this happening?

McKibben also quotes Ray Kurzweil, Google’s Director of Engineering, who says that, “We’ll have a synthetic neocortex in the cloud. We’ll connect our brains to the cloud just the way your smartphone is connected now.” This crazy future is one that people in the tech sector are trying to create. If humanity doesn’t like what they’re doing or the future they’re dragging us towards, then the tech industry must be forced to stop through regulations and internationally binding legislation.

1.10 Robotics

If humanity has evolved over hundreds of thousands of years without the need for either AI or robots, it’s safe to say that we don’t need them to survive or thrive.

We’ve seen the terrifying videos coming out of companies like Boston Dynamics. They’re just one problem, as many other types of robots are also being developed. In the Guardian Live event, Stuart Russell talked about how Amazon is trialling a picking robot in their warehouses. Should this be used to replace human pickers, one million people could lose their jobs.

As robots replace more jobs, Russell warns in Human Compatible that it could push wages below the poverty line for people who are unable to compete for the ever fewer higher skilled jobs that remain. Could this be just around the corner for society?

Russell said in the Guardian Live event that he expected the ‘robotics dam’ to break soon. So, be prepared for these monstrosities to become widespread and for worker replacements to rise rapidly.

1.11 Killer Robots

Killer robots, slaughterbots or AWS (lethal autonomous weapons systems) are types of weapons that can kill people, with no human intervention required. There is major interest in this type of AI technology from militaries as a new Netflix film (UNKNOWN: Killer Robots) shows. Some people believe lethal autonomous weapons systems are the future of warfare, despite the plethora of ethical issues.

It’s believed that the first documented use of a killer robot was in Spring 2020 in Libya. The first documented real life use of a swarm of drones guided by AI was in May 2021 (they were used by Israel in Gaza). The Autonomous Weapons website says there have been “numerous reports” of killer robots being used around the world, since those first two incidents. This shows that killer robots aren’t a future threat, they’re an existing risk that will only become more pronounced and deadly as time goes by.

Not only could these types of weapons be used by authoritarian regimes to kill large numbers of dissidents, activists, rebels, or protestors, but they can also be manipulated by AI if there was ever a war against humanity. In Human Compatible, Stuart Russell said, “superintelligent machines in conflict with humanity could certainly arm themselves this way, by turning relatively stupid killer robots into physical extensions of a global control system.”

In a testimony to the House of Lords committee on killer robots, a contributor warned that, “The use of AI in defence “presents significant dangers to the future of human security and is fundamentally immoral””, according to the inewspaper. The article also says that, mixing AI with weapons “poses an “unfathomable risk” to our species, could turn against its human operators and kill civilians indiscriminately.” Thus, slaughterbots don’t need to be like Arnold Schwarzenegger in the Terminator movies to be a threat.

Slaughterbots Videos

The Future of Life Institute with Stuart Russell released a short film about killer robots that went viral in 2017. The video was intended to serve as a warning of the direction these weapons were heading in, and feels reminiscent of something you might see on a Black Mirror episode.

Following the massive interest in the first video, which shows how things can go wrong with AWS, a second video was made. In this one, humanity narrowly escapes a chilling future by coming together to create international regulations on these automated death machines.

Risks and Issues with AWS

The Stop Killer Robots campaign lists several issues with AWS including:

- Algorithm biases mean that certain groups of people could be unfairly targeted

- Lack of accountability

- A lowering of the threshold for warfare

- A new (AI) arms race

The Autonomous Weapons website, adds additional risks including:

- They are unpredictable and can they behave strangely in real life. The unpredictability is also designed in to make it harder for soldiers to work out what they’ll do next

- There is potential for conflicts to rapidly escalate when these weapons are deployed

- They don’t understand the value of a human life, so shouldn’t have the power to kill

ICRC Solutions

The International Committee of the Red Cross has set out a list of recommendations on AWS including:

- Unpredictable AWS should be banned

- There should be limits on the kinds of AWS targets

- Using AWS to target humans should be banned

- The duration of use and the scale upon which AWS is used should be limited

- AWS should only be allowed in certain situations (e.g. avoiding use in environments with humans present)

- AWS should be required to have interactions with people, for supervision purposes

2. The Climate Crisis

“If the unchecked and accelerating combustion of fossil fuel was powerful enough to fundamentally change nature, then the unchecked and accelerating technological power observable in Silicon Valley and its global outposts may well be enough to fundamentally challenge human nature.” – Bill McKibben, Falter

Humanity has a knack for making completely unnecessary problems for itself. World War 1, World War 2, nuclear weapons, pesticides, CFCs and the hole in the ozone layer, climate breakdown, and now AI and the techopalypse, to name just a few. A small minority of humans always seem determined to continuously ruin things for everyone and everything else.

It’s worth noting that the climate crisis is the biggest issue our species has ever faced, perhaps only to be outpaced in the near future by the AI techopalypse. But the climate crisis will require our committed and determined attention over many years. We simply don’t have the bandwidth to manage another civilisation-altering (or civilisation-ending) emergency on top of this. This is why the AI crisis must be prevented at all costs.

For any individual saying that AI can give us solutions to solve the climate crisis, the truth is we already have the solutions and everything we need to tackle this problem. What we lack is political will. So that argument no longer holds water. And while we’re talking about AI and climate breakdown, AI requires massive servers which use significant amounts of energy and water. Unless that energy is coming from renewables, then AI is actually driving the climate crisis – another reason (if we needed one) to stop its development.

I won’t go into depth on the climate crisis, as plenty of my blog posts do that and can be read here. The reason why climate chaos is being mentioned at all, is because it has to be the issue humanity throws everything at given the threat it poses – we genuinely don’t have the capacity to deal with the climate crisis and another civilisation-eliminating issue like AI.

While the summer of 2023 has provided many climate stories of its own with hellish heatwaves, unrelenting wildfires, record-breaking ocean temperatures and a whole lot more, I’ll only write here about one other significant climate issue. It concerns news that by 2030, two billion people could be located in areas that are too hot to live in. Out of those two billion, it’s estimated that one billion people will chose to move. This means migration and immigration on a scale like nothing we’ve seen in history. And it will begin happening in just a few years. Where are one billion people going to move too? Which countries will offer these people refuge? How many wars will break out to keep people out? How many right-wing anti-immigrant politicians will rise to power because of this? What will that mean for democracy? Will those right-wing politicians embrace AI and get in bed with tech companies to maintain their stranglehold on power? What will that mean for all of us?

The fossil fuel companies, tech companies, politicians and the media have planted the seeds for a multi-faceted simultaneous catastrophe, which eight billion people will need to deal with. We will need everyone – every human, to play a role in saving our civilisation.

3. Solutions

“We cannot trust our destinies to machines alone. Man must make his own decisions.” – Louis L’Amour, Education of a Wandering Man

Humanity has historically taken a very reactive approach to world problems, whether that be world wars, nuclear weapons, the hole in the ozone layer, or the climate crisis. We allow a problem to develop, then scramble to fix it. With AI, AGI, and related technologies, we simply can’t take that approach. The reason being that if we develop AGI without being able to control it, then it would likely eradicate the human race as one of its first priorities. Even narrow AI is being developed which could eviscerate the jobs market and leave a billion people out of work. Such technology shouldn’t be developed, never mind being deployed, without wider debate and wholehearted societal support. After the AI horse has bolted, we won’t be able to get it back in the pen. And right now, the horse is galloping towards the open gate. Whether we choose to close that gate in time, will determine society’s fate.

Plan A – The Logical Solution

Considering all the issues we’ve explored from the copyrighted training data, the challenges of machine learning, the lack of control embedded in AI, the fact that we don’t fully understand how they work, the potential demise of art in all its forms, the risks posed to society and democracy, the loss of up to a billion jobs, the potential for cybercrime to rapidly escalate, AGI and the potential for human extinction, the loss of thought privacy through neurotechnology, the merging of humans and machines in biotechnology, the robotics dam about to burst, and the ethical issues around slaughterbots, some people believe there is a logical solution to hand – cease AI development and rollout with immediate effect.

Eliezer Yudkowsky has worked on aligning AI since 2001 and is a researcher at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute. In an article for Time, Yudkowsky was blunt with his recommendation, “Shut it all down.” Stuart Russell talked about this idea in his book in 2019, but came out against it because he didn’t want people telling AI researchers what they could and couldn’t research. Yet in 2023, given the rapid development and rollout of AI, Russell added his name to an open letter calling for a minimum of a six month pause in AI, to allow society and regulations to catch-up. Thus, it seems even Russell’s views are changing.

Yudkowsky’s solution is by far and away the most logical one (especially given that we don’t need AI). If we want to talk about human progress, what a story it would make – humans realise that they’ve developed a new extremely dangerous technology and uncharacteristically came together in unity to ban the technology and prevent it from causing widespread harm. This would be a monumental achievement for humanity, for which we could all be very proud. What a great legacy to leave for future generations.

But this logical outcome almost definitely won’t happen, because tech companies are motivated by profit, and governments want technological superiority over their rivals. To prevent this logical solution from being implemented, people in tech will continue expounding on the benefits of AI, so as to keep the wool firmly over society’s eyes.

Plan B – Other Solutions

After eliminating the most sensible solution, we must scrape the bottom of the barrel for a chance to at least have a future which might maintain a bit of what makes us human.

AI is developing so rapidly that many of the seemingly future-facing questions posed in this article need to be answered in the here and now. It most certainly isn’t for the tech industry to determine how this story plays out, especially when our culture and our civilisation are at stake. It’s for society as a whole to make that call.

There are ways for this to be done in a fair and democratic manner. One such option is through a global citizen’s assembly on AI. This is where members of the public are randomly selected to participate in the assembly (and it’s ensured that they are representative of the socio-economic make-up of each place). Experts provide information on both the benefits and threats of AI. At the end of the assembly guidelines are drawn up in a final report by the participants. These guidelines would ultimately be used as a basis for global regulations on AI development and deployment. Any company or government then has the ability to develop AI in line with these regulations, but not outside them, regardless of what investors or company growth forecasts demand. This is the fairest way of letting the world decide what we do or don’t want from AI.

Another solution comes from Hannah Fry and relates directly to people working in tech. Doctors are held to a high standard as they have human lives in their hands. As we’ve seen, tech workers are now in the same position as they take us towards the techopalypse. As such, it would make sense to implement Fry’s suggestion of having tech workers take a Hippocratic oath. One where they promise to do no evil, are duty bound to adhere to regulations that are based on the outcome of the citizen’s assembly, and ultimately call out any breaches of said guidelines within their organisations.

Related to this is the idea of taking power away from tech companies altogether. Some experts have suggested that the competition between tech companies is preventing the collaboration we desperately need to avoid disasters. This is apparently causing anxiety for tech developers. So, a solution could see AI developers in companies and governments working alongside academics to stay within safety guidelines. There have been calls for independent bodies to be created to examine AI code prior to release. These bodies could work alongside the developers and academics to mitigate safety issues as far as possible.

The website PauseAI recommends the following solutions including:

- Banning the training and building of AI more powerful than GPT4, until safety and alignment is assured

- Monitor GPU and hardware sales to enforce the ban

- Ban AI from being trained by copyrighted work

- Create an international AI safety body, much like the IAEA for nuclear weapons

- Grow the number of AI safety researchers on a national level

- Ensure that AI creators are held accountable for any criminal acts that are committed by their AI systems

Eliezer Yudkowsky’s other suggestions in the Time article include:

- An indefinite moratorium on big training and scraping runs, which are used to teach AI

- Close large computer farms and GPU clusters

- Put a limit on computer power usage for training AI (and move this limit downwards)

- Apply the thinking above to both the military and tech companies developing AI

- Create international agreements to prevent outsourcing this problem to a different country with weaker regulations

- “Be willing to destroy a rogue datacenter by airstrike.”

- Framing of the problem must focus on an AI arms race being detrimental for all

- On an international level, make it clear that the threat of extinction by AI supersedes nuclear war

To these ideas, it may be worth adding:

- Compensating creatives and people who’ve already had their work scraped

- A ban on AI for producing writing and art in any format

- A complete ban on using AI for political campaigns or any political purposes

- New legislation to prevent workers from being replaced by AI and massive fines for any company that tries to break that rule

- Internationally binding legislation to prevent the development of AGI, seeing as we can’t even manage narrow AI and we’re still trying to understand how it works

- The cessation of all developments in neurotechnology and biotechnology aside from those which have a genuine medical purpose. These medical developments should be jointly handled by a collective including doctors, researchers, academics, international organisations like the UN and independent safety bodies to ensure that the technology doesn’t stray from this single purpose

- A ban on robots

- A complete ban on killer robots

Overcoming Denialism in the Tech Sector

Stuart Russell writes in Human Compatible, that there is a type of denialism around AI in the tech industry with some people believing that it’s overhyped. This is quite bizarre given the progress already seen in the field of AI, and Russell attributes this to, “tribalism in defense of technological progress.” Some people say that AGI is decades away from being achieved. But Russell says we should never underestimate human ingenuity. He gives the example in Human Compatible of how, “liberating nuclear energy went from impossible to essentially solved in less than twenty-four hours.” That story can also be read here. Thus, the AI threat is very much a real and present one.

Others change tac and argue that technology has always resulted in profound change, just look at the industrial revolution, or look at what cars did for horses as a mode of transportation. But the KPMG report makes it clear that AI represents “a radical shift from past trends in automation.” We’re in completely unknown territory as such.

Help may not come from within the tech sector, so it’s up to all of us to do something about this. The best thing that all of us can do is talk about AI and the risks it poses. Talk about it with family, friends, and work colleagues. Talk about it with your MP or local political representative. In an interview with the Guardian, Geoffrey Hinton said that the reason why we’ve avoided disasters like nuclear war is because people “made a big fuss”, which resulted in overreactions and that led to us putting in place safeguards to avert disaster. Hinton said it’s better to overreact than underreact in these situations. That is one of the reasons why I’ve written this comprehensive blog post.

Regulating the Tech Industry

Stuart Russell also argues in Human Compatible that, the foundations of AI systems haven’t been built with human control in mind. IRL is a clear example of that. Although even CIRL (the solution to IRL) still has unsolved problems. As such, Russell says, “We need to do a substantial amount of work… including reshaping and rebuilding the foundations of AI.” This should be a priority, even if it means starting from scratch for tech companies. But they won’t voluntarily start from scratch even if that’s the only sensible solution on the table. Therefore, regulations must be put in place for these companies to abide by.

Unfortunately, in the Guardian Live event, Stuart Russell mentioned that the tech industry has already started lobbying against AI regulation. Adverts have appeared on TV in the US, against regulations. This is sadly nothing new. In The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Shoshana Zuboff writes about how tech companies have been lobbying for years on a range of issues. Zuboff says that Google is one of the richest lobbyists in the EU, and that in the US they spend more than any other tech company on lobbying.

Zuboff writes that, “Google and Facebook vigorously lobby to kill online privacy protection, limit regulations, weaken or block privacy-enhancing legislation, and thwart every attempt to circumscribe their practices.” She also refers to a Wall Street Journal article from July 2017, saying that, “Google had actively sought out and provided funding to university professors for research and policy papers that support Google’s positions on matters related to law, regulation, competition, patents, and so forth.”

The longer the world waits to regulate AI, the greater the stranglehold that tech companies will have and the harder it will become – especially given their track record. This sadly feels very reminiscent of how the fossil fuel industry lobbied heavily and ‘bought’ politicians to prevent regulations on their products, which has left us facing a climate catastrophe. We must learn from these mistakes as we can’t go through this again with tech companies.

Realising that regulation might be on the horizon, some tech companies have come together with the proposal of creating their own body to regulate the industry. But this isn’t anywhere near sufficient, nor is it to be trusted. Imagine if a premier league football team asked one of their players to put on a referee shirt and referee their premier league matches. You rightly wouldn’t trust the referee, nor would you expect a fair result. Any regulatory bodies should be entirely independent of the tech companies, and should have power to do what they feel is necessary to keep society safe.

4. Conclusion

“If the risks are not successfully mitigated, there will be no benefits.” – Stuart Russell, Human Compatible: AI and the Problem of Control

History shows us that sometimes a generation is called upon to solve a massive challenge. We may have pulled a very short straw indeed having to tackle two simultaneous issues at once in the climate crisis and the AI techopalypse, where failing to address one or both could result in complete disaster. Our failure in a best case scenario, would make the future very unpleasant for today’s children, and in a worst case scenario would deprive them of any kind of life resembling what we have. So much responsibility rests on our shoulders, but few realise this and even fewer are trying to make a difference. This simply must change – that is the only option on the table. Parents and grandparents should take note as you have more of a stake in the future than anyone else.

I’d encourage people to think of generations who’ve come before us and sacrificed so much to give us the freedoms we have today. People who stood up against slavery, against apartheid, against oppression and tyranny. People who fought in world wars and died for us. Our freedoms which have been hard won are in jeopardy of being lost forever. Through developments in neuroscience, we may not be able to have private thoughts for much longer. Through narrow AI, we might only consume culture that certain companies or governments want us to consume. Our democracies may stumble into dictatorships, as AI manipulates voters towards certain parties. The ability to get a job may become a gauntlet that few are able to get through. Police states with robots watching our every move could become commonplace. And our safety may forever be compromised by killer robots which may flood the black market, making murder easier and less traceable.

Parents have to plan for their children’s future and set them up as best as they can for life. But without fighting to reign in AI and tackle the climate crisis, they might effectively be preparing kids to inherit an environmentally and technologically wrecked world.

We have always been a reactive species, but AI requires us to be proactive and do something before a disaster unfolds, for if it does, it could be the last one in our troubled history.

Indifference

Many people don’t understand the nature of the threats we face, and it’s up to all of us to ensure that changes. Zuboff writes in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism about Langdon Winner, who says, “We have allowed ourselves to become “committed” to a pattern of technological “drift,” defined as “accumulated unanticipated consequences.” We accept the idea that technology must not be impeded if society is to prosper, and in this way we surrender to technological determinism.”

This folly could be our ultimate undoing, whether by completely reshaping society, or by ending civilisation entirely. The changes that need to be made involving citizens assemblies and a whole host of regulations, can only come from political leaders. But history shows us that citizenry often has to demand action. This is therefore the moment in time when all of us must become active citizens in the democratic space, and demand action.

Becoming an Active Citizen

I’ve spent fourteen years in the climate field. I’ve done a degree in the subject, been on countless marches (before the government put in place anti-democratic legislation to stifle protest and criminalise protestors), attended climate lectures/workshops/events, worked in the energy efficiency and offshore wind industries, read god-knows-how-many books/research papers and articles on the subject, donated a substantial amount to environmental charities, done all the small things like writing to politicians and signing petitions, and spent the last six years specifically teaching myself how to write stories about the climate and ecological crises to educate, engage and inspire widespread climate action. I can never put into words the toll the past fourteen years have had on my wellbeing. Nor do I even really know what I’m fighting for anymore. But still, I’ve kept going – because it’s the right thing to do.

But now with the AI techopalypse about to pile drive humanity into oblivion, I feel utterly deflated. Even Chris Nolan, the director of the Oppenheimer movie, has said that there are “very strong parallels” between Oppenheimer’s call for scaling back on nuclear weapons, and AI experts calling for curbs on AI. The chance of us being able to overcome one potential civilisation-ending crisis appear to be low, given that we’ve failed to address the climate emergency for 35 years. But the chance of overcoming two potential civilisation-ending threats simultaneously, seems a stretch too far. The heart-breaking irony is that both the climate crisis and the AI crisis are human-made. Both were completely unnecessary and both could’ve been avoided. It’s just the greed of the fossil fuel companies and the tech companies (both of which rank amongst the wealthiest companies on the planet), that have brought us to this point of reckoning.

In times of war, soldiers are occasionally given R&R opportunities (when it’s feasible), as reinforcements take their place. But after 14 years in the climate fight, I’ve been depressed to see that those reinforcements have yet to materialise and those of us on the frontlines are absolutely spent. I attended the biggest climate march in history in 2019. It involved around four million people protesting in 185 countries around the world. Four million sounds like a lot, until you consider that there were 7.7 billion people in the world in 2019. In other words, for the biggest climate protest in history, only 0.05% of humanity showed up. That’s soul-destroying. We need your help. Humanity needs your help – please.

The only good news is that as a global collective, we have the power to determine how the future plays out. What each of us can do is constructively engage with our political representatives to call for AI regulations (and climate action). There are many solutions out there – including those I covered in the ‘Solutions’ section. We keep going until the laws are put in place. It’s not complicated, but it will require perseverance and persistence. It feels impossible, but it can be done. It must be done. I wholeheartedly believe that when humanity comes together we can achieve remarkable things.

Research has shown that the critical threshold is 25% of the population demanding change. One in four people giving a damn about the future – giving a damn about society, rather than just themselves. Is that really too much to ask? If it is, then maybe everyone already on the climate battlefield and those stepping onto the AI battlefield should call it a day and let the forces of hell reshape the world. After all, why should some of us fight when other people, even those with a big stake in the future haven’t lifted a finger? It’s not fair for a tiny minority to carry this crippling burden.

Despite the scale of the challenges we face, what is being asked of us pales in comparison to the ultimate sacrifices made by so many people in world wars. Let’s put our excuses aside and focus on more action, more engagement, and more involvement as active democratic citizens.

In times of world war, people are enlisted to fight. If you’ve read this far, consider this an enlistment call. You are needed more than you can imagine. We either fight as global collective, or we ignore the blaring alarms around us and fail together. The clock is ticking, the history books are being written, and the window for action shuts a little more.

Friends, it’s time to win these wars once and for all – united we must stand.

Selected Resources

Books

- Human Compatible: AI and the Problem of Control by Stuart Russell

- The Alignment Problem: How Can Machines Learn Human Values? by Brian Christian

- Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out? By Bill McKibben

- Permanent Record by Edward Snowden

- The People Vs Tech: How the Internet is Killing Democracy (and how we save it) by Jamie Bartlett

- The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power by Shoshana Zuboff

- Life 3.0 by Max Tegmark

- 1984 by George Orwell

- Superintelligence by Nick Bostrom

Articles

- Stuart Russell – AI has much to offer humanity. It could also wreak terrible harm. It must be controlled

- Yuval Harari, Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin – You Can Have the Blue Pill or the Red Pill, and We’re Out of Blue Pills

- Jeremy Lent – To Counter AI Risk, We Must Develop an Integrated Intelligence

- Alex Hern – Interview – ‘We’ve discovered the secret of immortality. The bad news is it’s not for us’: why the godfather of AI fears for humanity

- Naomi Klein – AI machines aren’t ‘hallucinating’. But their makers are

- Yuval Noah Harari – Yuval Noah Harari argues that AI has hacked the operating system of human civilisation

- Eliezer Yudkowsky – Pausing AI Developments Isn’t Enough. We Need to Shut it All Down

- Jonathan Freedland – The future of AI is chilling – humans have to act together to overcome this threat to civilisation

- Ian Hogarth – We must slow down the race to God-like AI

- Harry de Quetteville – Yuval Noah Harari: ‘I don’t know if humans can survive AI’

- Lucas Mearian – Q&A: Google’s Geoffrey Hinton — humanity just a ‘passing phase’ in the evolution of intelligence

- Alex Hern and Dan Milmo – Man v machine: everything you need to know about AI

- Society of Authors – Publishers demand that tech companies seek consent before using copyright-protected works to develop AI systems

- Society of Authors – SoA survey reveals a third of translators and quarter of illustrators losing work to AI

- Ryan Mizzen – Boycott Generative AI Before AI Makes Your Career Boycott You

Podcast

Other

- Pause AI campaign

- Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter

- Restrict AI Illustration from Publishing: An Open Letter

- Statement on AI Risk

- Open Letter to Generative AI Leaders

- Autonomous Weapons Open Letter: AI & Robotics Researchers

- Lethal Autonomous Weapons Pledge

- Stop Killer Robots

- Amnesty International – Stop Killer Robots

- autonomousweapons.org

Template for Contacting Political Representatives about AI

Dear

I’m writing in regards to the rapid advances in AI and related technologies, which pose massive threats to society, jobs, arts and culture, democracy, privacy, and our collective civilisation.

Many AI systems are trained on copyrighted data and this has been done without consent or compensation. The way that machine learning works is flawed and this means that control hasn’t been designed into AI, which could create unimaginable problems further down the line. But AI isn’t just a future threat. The large language models (LLMs) already in the public domain threaten the livelihoods of writers and authors. AI image, video and audio generators pose risks to the jobs of artists, actors, and musicians. When combined together, these types of AI can have a devastating impact on democracy, and ‘deepfakes’ could be used by malicious actors for cybercrime purposes.

Both AI and the introduction of robots into the workforce jeopardises jobs on a scale like never before. By one estimate, up to a billion jobs could be lost, with only around ten million new jobs created. Mass unemployment could result, leading to social unrest, extreme poverty, and skyrocketing homelessness.